Archiver

Notes from Archive(r) at the Royal College of Art

30 September, 2019

Sekula:

The central Artefact of [Bertillion's] archive is the filing cabinet, not the photograph.

Archive as a body of literature independent of the objects inside it. All the descriptions, titles (written by archivists, not artists), but also categories, access status, reference numbers and so on.

Tate Archive contains different collections:

- TG - Tate Public Records

- TGA - Tate Archive Collections

- TAM - Tate Archive Collections on Microfiche

- TAP - Posters Collection

Microfilm Lasts Half a Millennium in the Atlantic

The search function has boolean logic: Heading must contain (term A AND term B) or (term C). Archive arithmetic.

There is a big long list of uncatalogued items. Must be hundreds, of not thousands of boxes. http://archive.tate.org.uk/TateArchiveUncatCollList.pdf

Things are organised on different levels:

- Fonds: the top-level record which gives an overview of the contents of a collection

- Sub-Fonds

- Series

- Sub-Series

- File

- Item: record containing information about one or more specific items

- Singleitem: a record describing a collection which only contains a single item

Found some kind of test item here.

A search for 'test' gives a few more of these. There doesn't seem to be a way to link to a search results page.

The website runs on something called DServe, which seems discontinued. Used to be made by Axiell. https://www.axiell.com/uk/solutions/archiving-software/

They sell all kinds of stuff for libraries and museums, including things like post-it notes.

Numbers

- 720 Fonds (Collections)

- 53 Sub-Fonds

- 2225 Series

- 4331 Sub-Series

- 25983 Files

- 92720 Items

- 1636 SingleItems

- 192 Pieces

The photographic collection (TGA) has images of all kinds of exhibitions, including random people's private collections. http://archive.tate.org.uk/tgaphotolists/TGAPHOTO7PrivateAndCorporateCollections.pdf

Some documentation on the digitisation process: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/archives-access-toolkit

Empty pages: Stuff that gets archived kind of by accident. Things between the historically important stuff.

Francis Bacon drawing that's almost nothing. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-9810-4/bacon-incomplete-letter-with-drawn-lines

- "Incomplete letter with drawn lines"

- "Extract from unidentified boxing magazine with photograph of Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney"

- "Page of text"

- "the page is black except for undistinguishable ink mark"

People wrote so many letters back in the day -- are we keeping artists' emails now?

Looks like things are kept in thr arrangement in which they're acquired (Collections). So, for instance, TGA 871 has some stuff from JMW Turner's studio, but also letters from the 1960s and someone's MA dissertation. Even when a collection comes directly from an artist, it often contains ephemera, letters from other people, reproductions of work, newspaper clippings and such. A collection of collections of collections.

- TGA 898/1/1

[see also Manovich re: re-arranging of pre-existing cultural material]

TGA 8421-1-6-6_10

TGA 8421-1-6-6_10

Blank Pages

- Front of postcards

The images have titles and other meta information in the EXIF fields. Digital image: more than just a visual record, has metadata baked right into it.

Who picks the featured images? I guess some of the goal here is to generate engagement (that's also what the process writing talks about).

Archive items are tied in / cross-referenced with other Tate data structures: Artists, finished works (which appear to live in a separate database, interesting where the distinctino lies there), "Features" (which are articles), and related artists (chosen by who knows what algorithm), tags.

Some things have lost all their context:

- TGA 779/8/94: Photograph of an unidentified man (1920-1960)

- TGA 779/8/111: Photograph of an unidentified building (1920-1960)

Everything has different licensing attached to it. Every item wound up in countless systems, paper trails

2 October, 2019

Records Continuum Model after Upward.

9 October

Spent an hour photographing shelves in the store — about 800 images in total, some usable.

- On labels: One archivist passing knowledge onto the next one. The archive as a body of writing / knowledge.

10 October

Borges (1993): The Analytical Language of John Wilkins:

These ambiguities, redundancies and deficiencies [in Wilkin's constructed language] remind us of those which doctor Franz Kuhn attributes to a certain Chinese encyclopaedia entitled 'Celestial Empire of benevolent Knowledge'. In its remote pages it is written that the animals aredivided into: (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame,(d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h)included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable,(k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way offlook like flies.

Obviously this isn't real (because that's what Borges does).

Foucault comments on the passage at length in The Order of Things (1966) saying the reason this is so funny/uncomfortable is that we can't imagine a space in which all of these categories can exist at the same time — they have no shared criteria, rules of sameness.

14 October

- Can manipulate the number of catalogue entries shown per page by passing

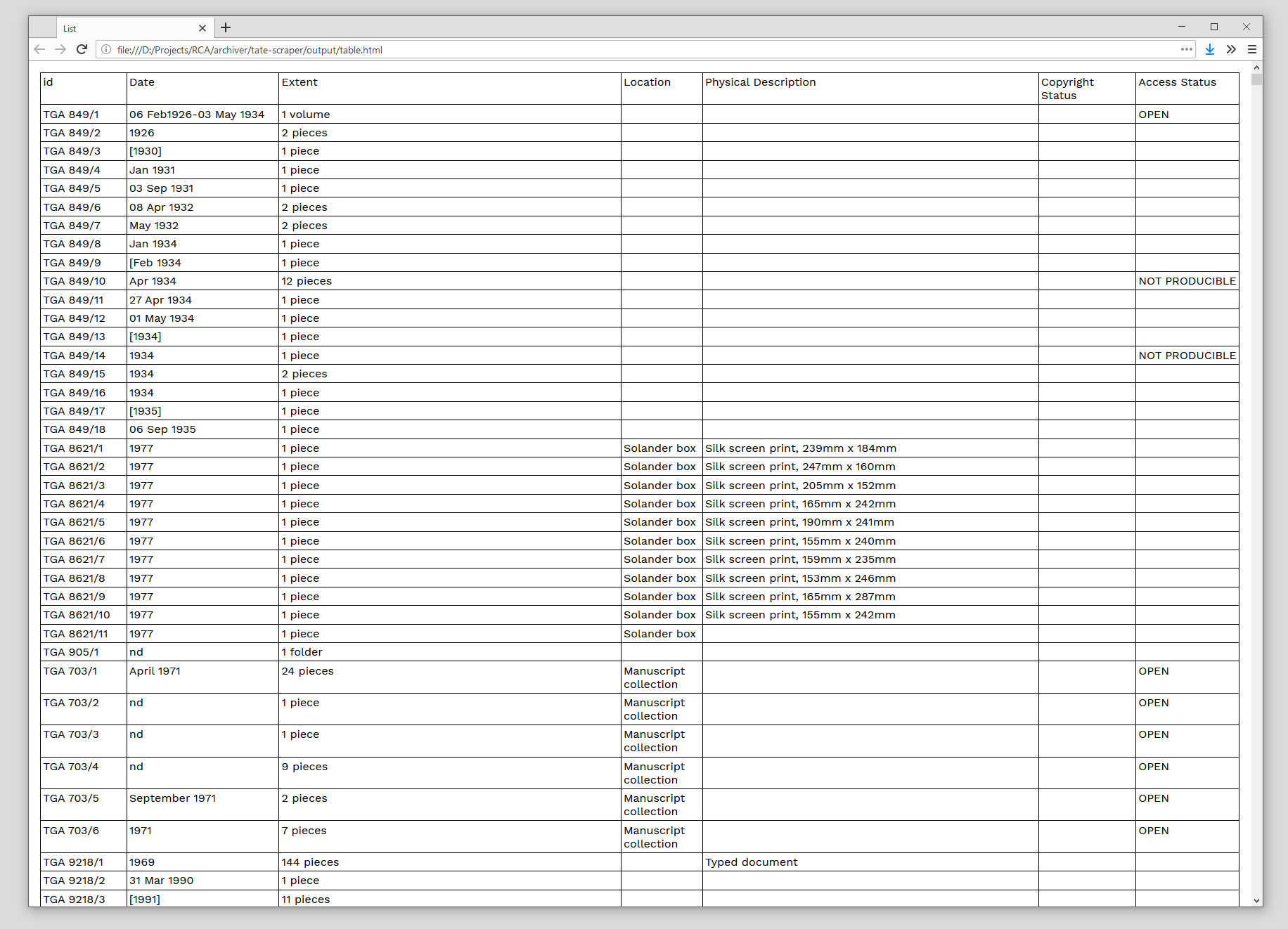

&dsqNum=50url parameter. - Completely scraped the online catalogue. Took about two days to write the puppeteer script — multiple runs required to merge top-level entries with lower level ones. Actual running time probably 3-4 hours. The final JSON file is 10.7MB — less than I expected.

- The online catalogue only goes two levels deep: Collections (of which there are 720) and whatever sits directly below them in the hierarchy. Sometimes these are

items, but many areseriesorfilescontaining more items for which no catalogue entries exist (at least no public ones). - Now that I have the data in a structured format, I can analyse it locally much more effectively.

- There is a huge discrepancy in the numbers of items I've scraped and the numbers I gathered on September 30 by searching the online catalogue.

30 October

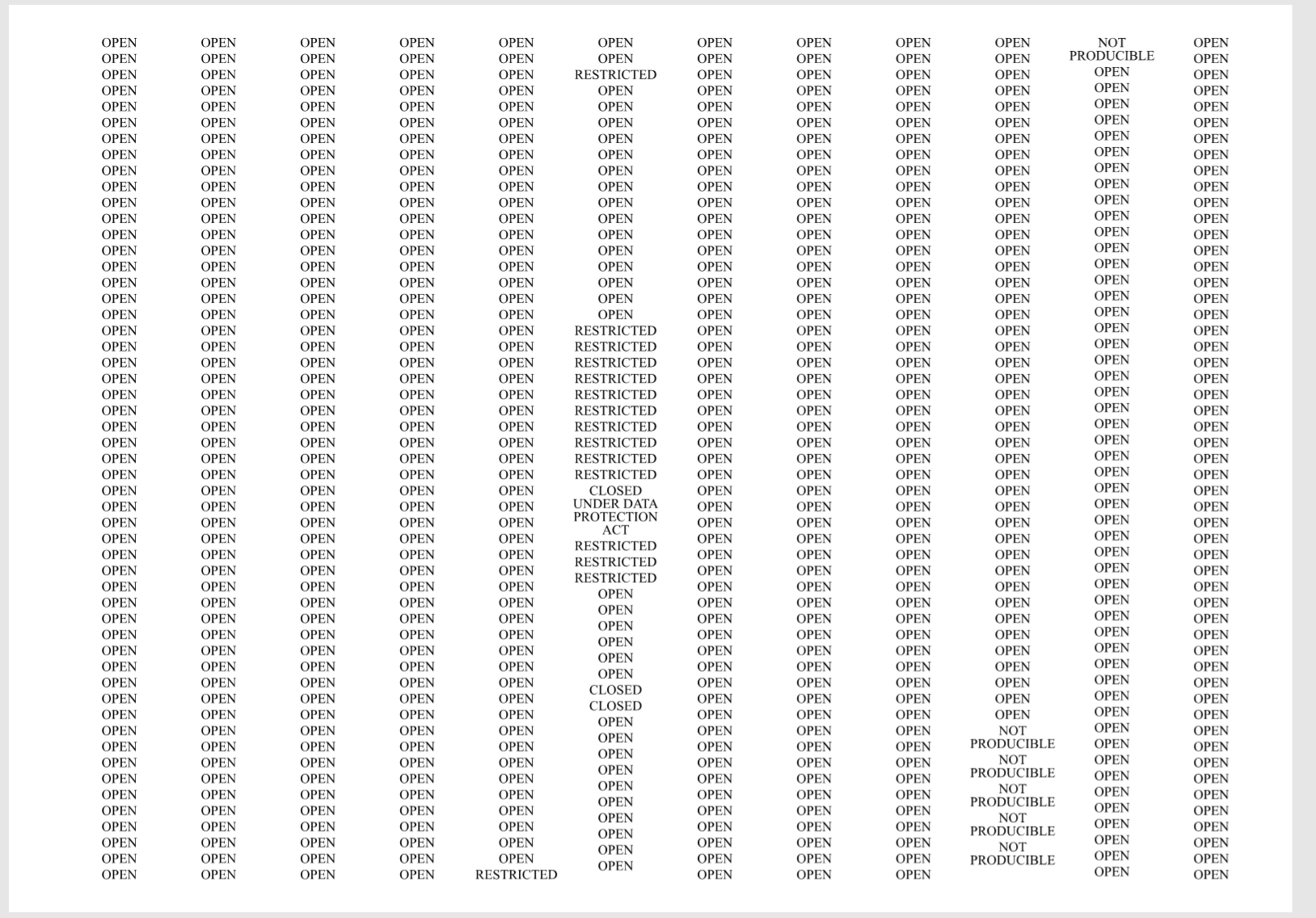

Fairly straightforward to go through all the second-level entries in my dataset and output lists of fields like Access Conditions and Acquisition History. Visually, this starts to resemble works like Codenames (2001) by Paglen, 5.12 Citizen's Investigation, and the list of migrants who died on their way to Europe.

List of access conditions

List of access conditions

- I like Paglen's piece for how abstract it is — the work uses journalistic methods, but the mode of address is more subtle.

- He's using that typeaface and centered columns to suggest war memorials

Scraped catalogue rendered as a long table. Note that not all data fields are represented here.

Scraped catalogue rendered as a long table. Note that not all data fields are represented here.

The archive as a layering of tables (using Foucaults notion of that term). Tables within tables within tables.

November 16

Montford (2003): Twisty little passages

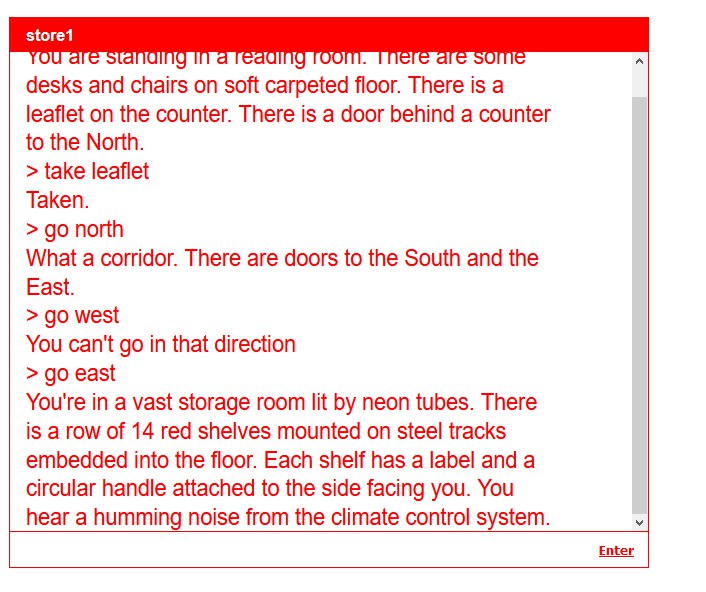

- We're making a text adventure because the primary material of the archive is text. Therefore it's an appropriate medium to explore that corpus - I don't need to translate or "visualise" anything.

- Also allows me to positively make something instead of doing just criticism for which I'm unqualified anyway.

- In the game, you play the archivist. Your goal is to find a certain item in the archive. The game world (or "map", which brings to mind Borges) is closely modeled on the real Tate archive.

- A large part of the language in the game comes from the Tate archive catalogue (which I've scraped). You'll be able to access any item on any shelf in the game and get information about it.

- The game is a way of approaching architecture, access, archival stationary, hierarchy at the same time.

Preface

Text adventures are a textual representation of some imagined game world (not unlike the archive itself).

The setting of an interactive fiction work [...] is more than a setting. It is a simulated world, which in practice is represented computationally in some sort of data structure or collection of objects. It is this simulated world that distinguishes a work of interactive fiction from a conversational character or from an expert system that employs natural language understanding. viii

- Two components: Parser and World Model

The world model is typically implemented in the interactive fiction program as some type of graph [referring to the mathematical model, which also aplies to the archive!] or tree structures of some sort (eg record, object, list) with associated procedures, methods, or functions (Graves 1987). ix

1: The pleasure of the text adventure

The person who reads and writes to interact is the "operator" of an interactive fiction in cybertextual terminology (Aarseth 1997); in general computing terms, this person is the "user". So as to emphasize that the actions of reading, writing, playing, and figuring out are all involved in such operation or use, the term "interactor" is used in this book. 3

- Parsers can range from "verb OR verb noun" to full NLP systems.

- IF can be understood as literature, game, software.

- Oulipo notion of potential literature

- One interaction with the program is called a session, a transcript of that interaction (including both the program and the interactor) is called a session text.

- Diegetic, extradiegetic and hyperdiegetic texts coexist in interactive fiction, ie:

- go west from the interactor is a diegetic command

- save game extradiegetic directive

- You are standing in a field from the program diegetic reply

- I didn't understand that word extradiegetic report

- Different levels of narration breaching each other is called metalepsis.

- A traversal of a work is a course that extends from the inital situation (the first thing the program writes on the screen) to a final reply. Also a term in graph theory, which makes sense.