Gradient Drawings

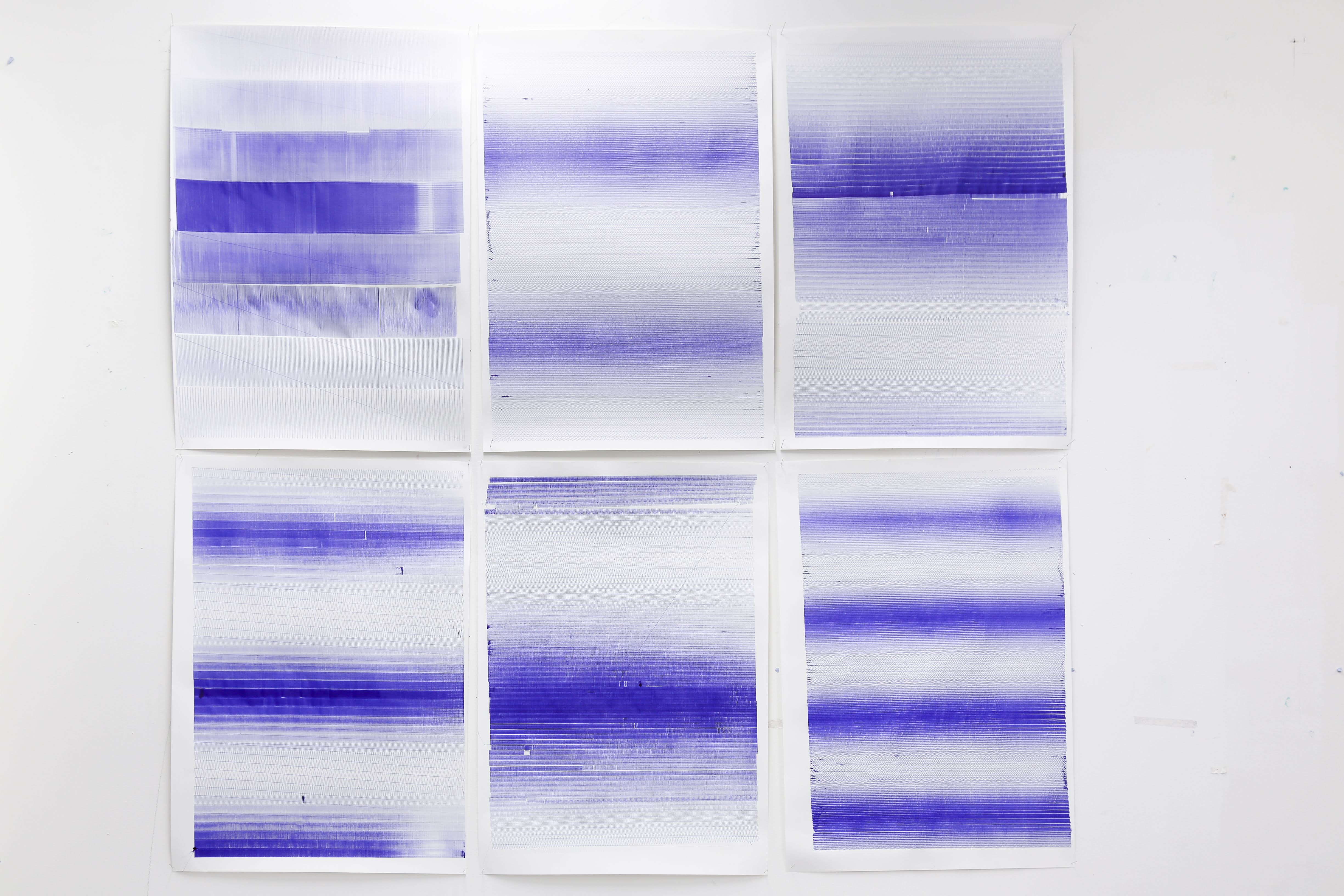

I started making machine drawings during my undergrad. Many of my early drawings where born from the excitement fo getting the machine to work at all. Suddenly, I could draw perfectly straight lines, repeat gestures hundreds of times and keep drawing for hours at a time. There's something oddly mezmerising about seeing a familiar drawing instrument (like a ballpoint pen) move in an unfamilliar way: slow, in long, straight lines and with even pressure.

Eventually I made another discovery: When I repeated a shape often enough (or stepped back far enough), the lines dissolved into shades of gray. I made some drawings that experimented with this, but they were never completely satisfying.

A few months after my graduation, an architect gave me a 1976 book on Iannis Xenakis, the modernist composer. The book covers decades' worth of work, but I was struck by a drawing of his from early in Xenakis' career, when he was still working in Le Corbusier's studio in Paris.

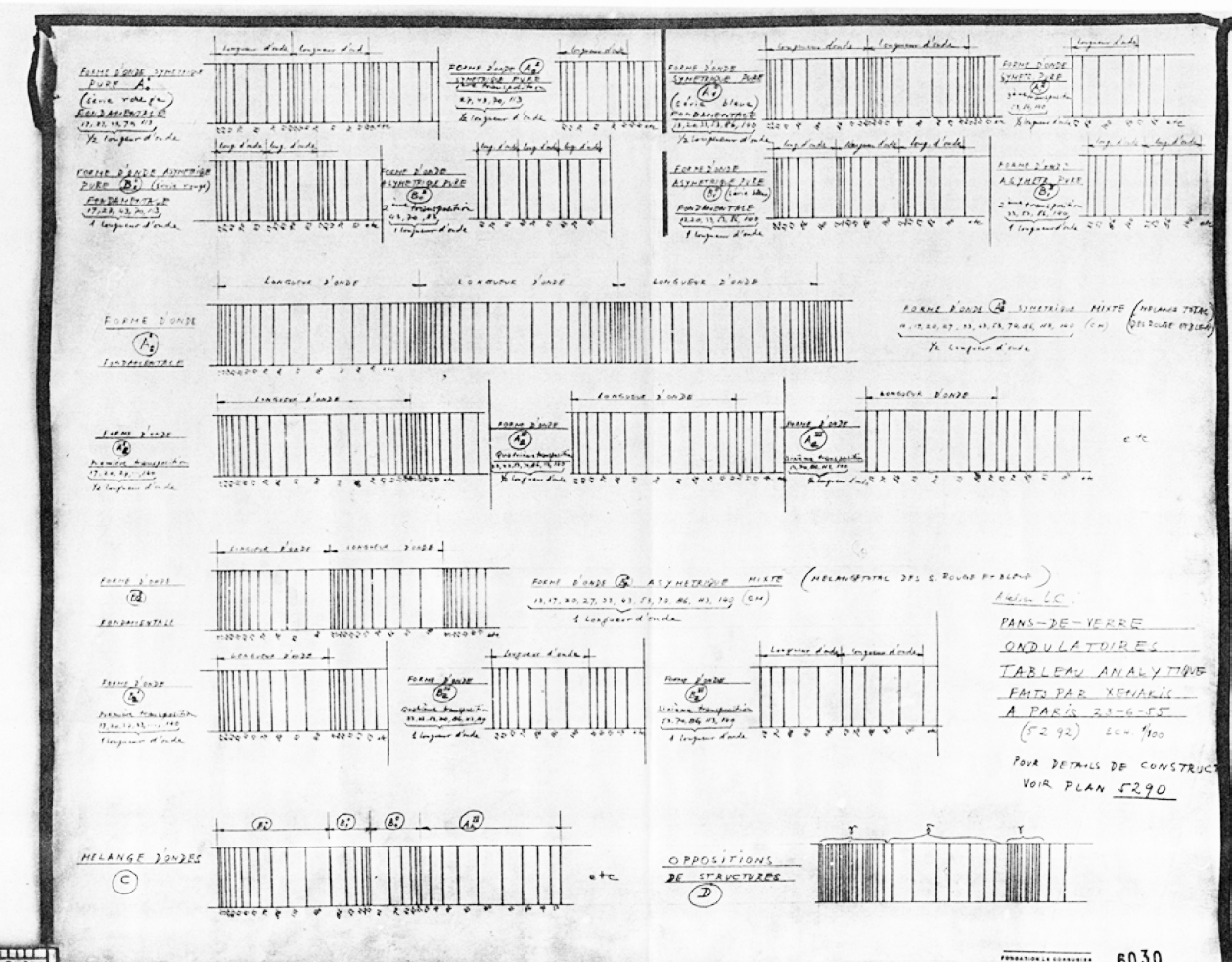

Iannis Xenakis, table with progressions of rectangles with increasing widths drawn from the Modulor. Source: Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris. Reproduced in Sterken (2007).

Iannis Xenakis, table with progressions of rectangles with increasing widths drawn from the Modulor. Source: Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris. Reproduced in Sterken (2007).

It shows a series of designs for the facade of the monastery of Sainte-Marie de La Tourette in southern France. Each of the 18 designs is unique, yet they all seem to come from some common system.

Iannis Xenakis and Le Corbusier: Sainte Marie de La Tourette. Source

Iannis Xenakis and Le Corbusier: Sainte Marie de La Tourette. Source

My understanding is that he derives these from a harmoic series based on the modulor series. High-resolution scans of Xenakis' drawings don't seem to exist (Even his own monograph suffers from poor reproductions), so it's hard to reverse-engineer the exact method he used to generate these patterns. the best I can tell, he's taking one number $x_0$, multiplying it with another one (presumably the golden ratio $\varphi \approx 1.618034$, since that's how the modulor is derived) to get a second one. The second number is multiplied with $\varphi$ again to obtain a third, and the process is repeated to create a series of $n$ numbers. In short:

$$x_n = x_{0} \varphi^n$$

Once the value of $x_n$ exceeds a certain threshold, he starts dividing by $\varphi$ instead of multiplying. Once $x_n$ becomes smaller than a certain value, he switches back to multiplication, and so on. I think he repeats this process for different values of $x_0$ and then combines the resulting series of numbers (by orderubg them by value) to obtain the final result.

The striking thing about Xenakis' method is that for all it's mathematical exactness and complexity, the result feels entirely natural. It is also worth pointing out that he's not really designing a facade: His project is really a machine for making facades. Between all the possible values of $x_0$, $n$ and $\varphi$, he opens up a facade space filled with an infinite number of points.

Xenakis' algorithm is relatively simple — yet it allows for essentially infinite variations. I saw in this a method to explore the tension between line and tone in my undergrad machine drawings in a structured way.

I began by writing a tool that would allow me to generate vector drawings following Xenakis' algorithm. I begin with a zig-zag line across the top of the page. For the second line, I take the number of zig-zags in the first and multiply it by a fixed ratio $\varphi$. The third line is derived by multiplying the number of zig-zags in the second with $\varphi$, and so on. Like Xenakis, I switch to division once a certain threshold is reached.

Xenakis (as far as I can tell) only used the Golden Ratio for his facades. I like using the 12 intervals in the harmonic scale, too.

| Interval in C | Ratio | Ratio (1:x) | % of larger value | % of smaller value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unison | C→C | 1:1 | 1 | 100 | 100 |

| minor second | C→D♭ | 15:16 | 1.067 | 0.9372071228 | 106.7 |

| major second | C→D | 8:9 | 1.125 | 0.8888888889 | 112.5 |

| minor third | C→E♭ | 5:6 | 1.2 | 0.8333333333 | 120 |

| major third | C→E | 4:5 | 1.25 | 0.8 | 125 |

| perfect fourth | C→F | 3:4 | 1.333 | 0.7501875469 | 133.3 |

| aug. fourth or dim. fifth | C→F♯/G♭ | 1:√2 | 1.414 | 0.7072135785 | 141.4 |

| perfect fifth | C→G | 2:3 | 1.5 | 0.6666666667 | 150 |

| minor sixth | C→A♭ | 5:8 | 1.6 | 0.625 | 160 |

| major sixth | C→A | 3:5 | 1.667 | 0.599880024 | 166.7 |

| minor seventh | C→B♭ | 9:16 | 1.778 | 0.5624296963 | 177.8 |

| major seventh | C→B | 8:15 | 1.875 | 0.5333333333 | 187.5 |

| octave | C→C | 1:2 | 2 | 0.5 | 200 |

Notes

- Owen Gregory (2011): Composing the New Canon: Music, Harmony, Proportion

- Sven Sterken (2007): Music as an Art of Space: Interactions between Music and Architecture in the Work of Iannis Xenakis. Available at core.ac.uk/download/pdf/34525212.pdf

- Alex Ross (2010): Waveforms: The singular Iannis Xenakis. The New Yorker. Available at newyorker.com/magazine/2010/03/01/waveforms