Dissertation Notes

Proposal (December 2018)

Provisional Title: The photographic image in the age of the neural network

Topic (approx. 100 words)

How does our understanding of the photographic image change when most photographs are taken by machines for machines? What happens to the photograph when it becomes an instance (of millions) in a machine-learning dataset, and are these datasets a modern extension of the photographic archive? How do we respond to images produced by machines (ie. operational images and, more recently, deep fakes)?

Research

There’s a rich body of literature on our relationship with the digital photograph (Steyerl, Farocki, Paglen) and the archive (Foucault, Sekula, Derrida, and more recent writers on instances of digital archives like the Enron Corpus, Facebook profiles, and various archive-related efforts by Google).

I’m hoping to base this cultural analysis on readings of papers from the field of computer science, both historical (such as Rosenblatt 1958, which introduces the concept of the neural network) and contemporary (such as Taigman, Yang, Ranzato and Wolf (2014), which describes the first image-classification model with human-level performance (developed by Facebook) and Nguyen, Yosinski and Clune 2015, which details how such models can be fooled using artificial imagery).

600-800 Word Text

If you can imagine it, there is probably a dataset of it. The "Machine Learning Repository", which is maintained by the University of California, lists 426 datasets at the time of this writing, each consisting of between hundreds and tens of millions of instances. A set of anonymised records from the 1990 U.S. census (24 million instances) sits next to one consisting of 150 hours of Indian TV news broadcasts (12 million instances). The 371 choral works of J.S. Bach (in machine-readable form) can be found next to cases of breast cancer in Wisconsin (699 of them), forest fires (571) just below Facebook comments (40,949) (University of California, Irvine). If we narrow the search to datasets of images, we still get countless results. There is the Stanford Dogs dataset (20,580, 110 breeds), the German Traffic Sign Detection Benchmark Dataset (900), and dozens of datasets of human faces. Arranged in chronological order, the face datasets tell us about the shifting economic circumstances of database production. The earliest face datasets are created by research groups directly engaged in facial recognition research, and predominantly feature whoever was walking around the laboratory at the time. The Yale Face Database (1997, 165 instances) and the Carnegie Mellon Face Images Dataset (1999, 640 instances) are examples of this. In the early 2000s, we start to see targeted efforts to generate face databases, now detached from researchers working on the algorithms themselves. The FERET database (2003, 11,338), which was funded by the U.S Defence Department is perhaps the most striking example of this. Though the number of instances has jumped by two orders of magnitude, the fundamental mode of production method hasn't changed from first phase of datasets: A professional photographer (hired for this purpose) is recording paid volunteers, for the sole purpose of creating material for the database. This relationship starts to change by 2010, when image databases are increasingly sourced from public sources on the internet using automated crawlers. This shift from original production to automated extraction of images allows the number of instances to increase by orders of magnitude again: FaceScrub (2014, 107,818) was compiled using Google's image search, IMDB-WIKI (2015, 523,051) and the Youtube Face Database (2012, ~600,000) bear their mining-grounds in their names.

The largest face dataset whose existence has been publicly acknowledged (at 4,000,000 instances) isn't even listed: it's Facebook's proprietary face dataset, which is not publicly available. By controlling the richest dataset, Facebook by extension controls the world's most powerful facial recognition algorithm (Taigman et al., 2014). How do we deal with the emergence of these vast datasets in cultural terms? It seems natural to place the database in the tradition of the photographic archive. But are they really the same? Sekula (1986) describes how the photographic archive of the 19th century serves to "define, regulate" and thus to control social deviance. The dataset certainly serves that function - one needn't look very hard to find countless examples of police, governments and corporations using automated image-making to sort people along scales of likely social compliance (Paglen, 2016) (Sekula, 1986). However, in some ways the database seems fundamentally different from the archive. First, the archive usually comes with an index (or catalogue) to help whoever is accessing the archive find any particular record (Berthod 2017).The dataset is essentially a flat list with no means of navigation other than sorting by filenames (which are often meaningless). This leads to the larger observation that in the database, the individual record is essentially meaningless. Only the accumulation of thousands, or millions of similar records make it useful - as Halevy et al (2009) show, the accuracy of an algorithm is directly linked to the quantity (not completeness, or even accuracy) of the training data (Steyerl, 2016). Secondly:

While both the archive and the dataset exert power, they do so in different ways. The archive controls primarily whoever is recorded in the archive (or conversely, whoever is left out). The dataset has no spatial or temporal limitations - a dataset of portraits collected in the Midwest in the 1990s might be used by a police computer on the other side of the globe, 30 years later. This is perhaps because the dataset, unlike the archive, is ultimately a means to an end: A raw, unrefined material from which algorithms might be forged. In this context the agricultural language surrounding the creation of archives and databases (as observed by Steyerl), seems to underline this point: The archive is curated, recorded, built-up, accumulated. Data is mined, harvested and crawled before truckloads of it are compressed, distributed and fed to the algorithm.

Bibliography

- Susan Leigh Star (2000): Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences MIT Press

- Hal Foster (2004): An archival impulse. Available from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3397555

- Nguyen A, Yosinski J, Clune J (2015): Deep neural networks are easily fooled: High confidence predictions for unrecognizable images. Available from evolvingai.org/fooling

- Yaniv Taigman, Ming Yang, Marc'Aurelio Ranzato, Lior Wolf (2014): DeepFace: Closing the Gap to Human-Level Performance in Face Verification. Available from research.fb.com/publications/deepface-closing-the-gap-to-human-level-performance-in-face-verification/

- Trevor Paglen (2016): Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You). Available from: thenewinquiry.com/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you/

- Allan Sekula (1986): The Body and the Archive. Available from: www.jstor.org/stable/778312

- Alon Halevy, Peter Norvig, and Fernando Pereira (2009): The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Data https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//pubs/archive/35179.pdf

- Hito Steyerl (2016): A sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis-)Recognition https://www.e-flux.com/journal/72/60480/a-sea-of-data-apophenia-and-pattern-mis-recognition/

- Rob Hornig (2018): Plausible Disavowal. Real Life Magazine. Available from: reallifemag.com/plausible-disavowal/ Charles Merewether (2006): The Archive: Documents of Contemporary Art. MIT Press

Non-print sources

Artists dealing with the operational image, databases etc:

- Farocki, H. (2001). Eye/Machine I. [Two-channel video installation re-edited to single-channel video (color, sound)] New York: Museum of Modern Art.

- Paglen, T. (2017). It Began as a Military Experiment [C-type prints]. New York: Metro Pictures

Various Image-Databases such as:

- National Institute for Standards and Technology (2003): Face Recognition Technology (FERET). [Database of digital images]. Available from https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/face-recognition-technology-feret

- Lior Wolf, Tal Hassner and Itay Maoz (2011): Youtube Faces Database [Database of digital videos]. Available from https://www.cs.tau.ac.il/~wolf/ytfaces/

Tutorial Notes January 15, 2019

- The proposal touches on different aspects of the same ontological question about the nature of photography in the digital age.

- It would be useful to start the text by establishing the existing discourse around photography (see James Elkins)

- Subsequent chapters can then deal with the problem from various angles

There is also the observation that thinking about how machines see the world forces us to question how we ourselves do it.

Chapters could be:

- Database vs the Archive as touched on in the proposal. Bertillion vs NIST.

- The idea that the act of looking at photographs is increasingly outsourced to low-paid workers. Also the view of data-mining companies (ie. social media platforms) as extractive industries.

- What happens when machines look at images (note the usage of the word look — not particularly accurate, but we don't have anything better.)

- What happens when machines make images for us to look at (although the main reason generative networks are being developed is to extend training datasets for other machines)

GAN / Youtube Faces Dataset

GAN / Youtube Faces Dataset

The main methodoligical idea remains to do this not just through sources from the humanities, but also understand the mathematics, physics, economics and logistics of machine vision.

January 16, 2018

Possible chapters / angles:

Data collection (how images are taken)

(Through sensors etc, driven by economy, some images start life as representations and become data) This would be where the reflection on the database vs the archive goes. Also a good place to do figures that update dynamically.

- Architecture

- Code (this is maybe the least interesting layer)

Mathematics (Network architecture and history thereof)

Assumptions can be hard-coded into architecture. This section should probably include an explanation of how common network architectures work, also a good place for live demonstrations. Maybe a text-to-image model? Or a pix2pix trained on line drawings.

Infrastructure (Cables, Buildings, Chips)

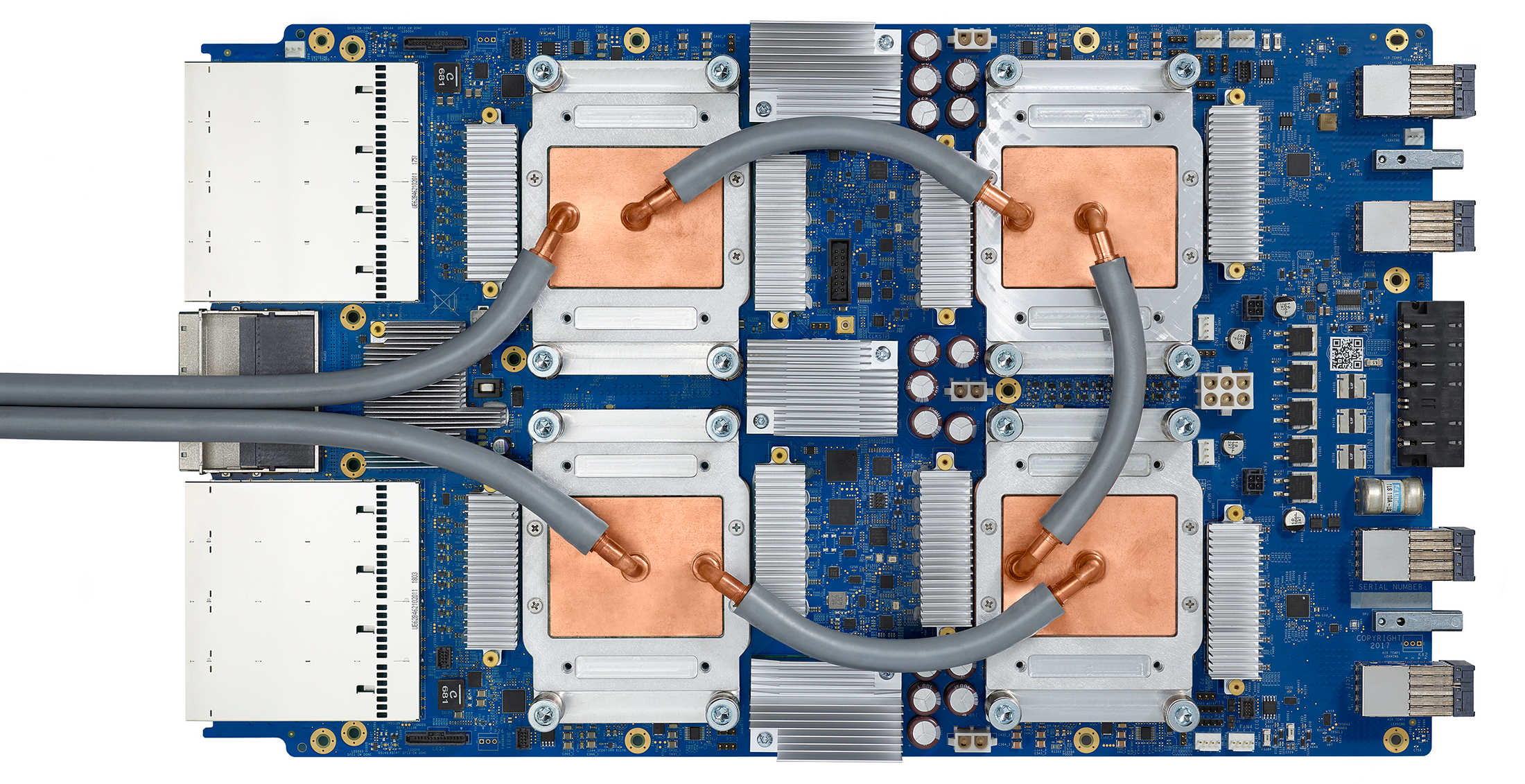

Google (and also Facebook) are building these dedicated processing units:

Third generation Cloud TPU Google

Third generation Cloud TPU Google

Labour (generating training data, reverse Turing test): Who looks at the images

There is this narrative that machine learning models spring from the minds of genius programmers. See for instance this Fastcompany article: It suggests a Google intern made this amazing model, when really the guy has a PhD and used thousands of pounds worth of computing power. And more broadly, the datasets, hardware, infrastructure etc. are propped up by much lower-skilled lablour.

A lot of papers use Amazon Mechanical Turk to validate results or generate training sets:

- The Atlantic: The Internet Is Enabling a New Kind of Poorly Paid Hell

Machines generating images

Maybe talk about a specific model: Pix2pix would seem to be a good candidate.

Group tutorial notes

Keywords (6-10)

- Archive

- Database

- Computer Vision

- Machine Learning

- Reverse Turing Test

- Digital Photography

- Operational Images

- Digital Economy

Map

a current ‘map’ of the dissertation (including key themes / writers / artists / examples)

I think it's probably necessary to talk about real-world examples of computer vision having social consequences, but the ultimate goal is to get to a more fundamental question: How do we have to look at photography in the age of the database? Also, the age of the database has been going on for far longer than neural networks have been in the public consciousness.

Images

Key Texts

- Barthes (1980): Camera Lucida

- Sekula (1984): The body and the archive

- Elkins (2011): What photography is

- Isola, Zhu, Zhou, Efros (2016): Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks

- Paglen (2016): Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You)

- Steyerl (2016): A Sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis-)Recognition

- Lecture notes from CS231n at Stanford

- Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences

New writing

a short piece of writing (approx. half a page / one page) that you are happy to share with the group. The writing doesn't need to be a summary of your thinking, it can be a new piece of writing that is responding to one of your key ideas... and it can be quite rough! It might be helpful to bring some text that you would like feedback on - whether it is the style of writing, the ideas contained within... or a combination of both.