Dissertation: How does the conflict between collectivist utopia and individualism in modernism manifest itself in housing architecture?

We remember the Bauhaus mostly for its physical artifacts: Steel tube furniture, household appliances put together from geometric shapes, New Typography, all set against the backdrop of flat-roofed, pristine white architecture. The philosophical and political struggle that led to these outcomes seems distant to us. Reading some of the Bauhaus publications, written in somewhat stilted 1920s German can only give us a faint idea of the monumental endeavour the Bauhausler were engaged in.

What they were working towards was vision for society in which citizens, architecture, product design, agriculture, entertainment, science and art would exist together in one unified, rational programme: Modernism. To the young people at the Bauhaus, overlooking the rising industrial town of Dessau from their glass-wrapped studios this idea must have felt utterly within reach: In a country still struggling to recover from the First World War, with violent revolutions going on in Europe and new technology changing every aspect of life, change seemed inevitable. (Wilder, 2016)

How exactly that change should look like, the Bauhausler never quite agreed on. The early Bauhaus was driven by the search for individual expression. Johannes Itten, with his head shaved and wearing a robe of his own design, taught the now-famous Vorkurs: Here, students developed their personal means of expression through meditation, philosophy and basic exercises (Bauhaus100.de, 2017).

The Bauhaus started to move toward a more collective outlook in 1922, when Theo van Doesburg, a proponent of De Stijl began teaching at the Bauhaus. He introduced the reduction to geometric shapes and primary colours that would come to define the "Bauhaus Style". The following year Hungarian artist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy took over teaching of the preliminary course. He replaced much of Itten's ecclectic curriculum with exercises using industrial material. In the following years, objectivity and scientific rigor remained the governing thought at the Bauhaus. It was during this later period that Marcel Breuer produced furniture out of precision steel tube, Marianne Brandt designed geometric household items and Walter Gropius completed some of the most iconic examples of modernist architecture (Droste, 1998).

Despite its academic success the Bauhaus was faced with political pressure from its inception. The increasingly right-wing government of Weimar forced the Bauhaus to move to Dessau in 1925. When the Nazis came to national power in the 1930s, the Bauhaus again to Berlin where, after a brief period under the leadership of Mies van der Rohe, the school disbanded in 1933. Many former Bauhausler were forced to flee Germany, which of course only served to spread Bauhaus ideas. Gropius, Breuer, Mies and others continued to teach in the United States, contributing to the emergence of the International Style. (Wilder, 2016)

The architectural legacy of the Bauhaus surrounds us to this day. I'm writing this from a 1960s university building with steel windows, concrete slab floors and curtain walls not dissimilar to what Gropius used 40 years prior in Dessau. Similar buildings can be found in cities all over the world. However, desipite its ubiquity, modernist architecture, particularly in the context of social housing, has been a point of contention for the better part of a century. Critics like Nikolaus Pevsner describe modernist housing developments as "impersonal and megalomaniac creations" (Fletcher, 2008), incapable of meeting the diverse needs of their residents. This gets to the conflict that this essay sets out to explore: The apparent contradiction between individualism the collectivist utopia of modernism — a contradiction that is deeply embedded within the modernist movement and the changing perception of its products over the course of the 20th century.

Two Conflicts

When we ask about the conflict between individualism and collectivism in modernism, we should start by defining the conflict. In fact, we can identify two different conflicts at play simultaneously: First, there is the conflict between the collectivist, egalitarian vision of modernism and the image of the heroic, sole creator (be it Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius or Mies van der Rohe) who is tasked to bring that vision to life. This is linked to Marianne DeKoven's (2011) analysis of modernism and gender, which places the myth of the (male) hero artist at the very centre of modernist thinking. Secondly, I'm going to examine the conflict between modernist architecture and the individualism of the people inhabiting it in the context of post-war consumerism. This conflict is defined on one side by the collectivist utopia of the Bauhaus: A world in which housing, transportation, appliances, culture and food is designed through a scientific process and mass-produced by machines to be affordable to everyone. By reducing forms to their functional minimum, the Bauhaus aimed to create universal solutions for housing, education and everyday life. On the other side is the populist critique of those universal solutions as being fundamentally at odds with the people's inherent individualism — a critique epitomised by the image of the derelict housing block. THis line of attack which originates in the 1970s with Oscar Newman's (1972) study "Defensible Space: People and Design in the Violent City", which links modernist housing with increased crime, arguing that the spatial design of housing blocks makes them inherently unsafe, and that private space, rather than public space should be prioritised. Newman's work has since been criticised for its overly broad assumptions about the nature of human interaction (Steventon, 1996). Popular critics such as Tom Wolfe (1981) criticise modernist housing as being overly academic and fundamentally unfit for its purpose. Wolfe cites the widely publicized demolition of the Pruitt–Igoe housing estate in St. Louis in 1972 (only 20 years after its construction) as evidence for the failure of the collectivist ideas of modernism. This popular rejection of modernist housing models on the grounds that it doesn't reflect people's individualism can be linked to the emergence of modern consumerism in the second half of the 20th century. As Miles (1998) shows, consumer culture emerges as a result of an increase in real wages and improved production methods suddenly making commodities available to large parts of the population. This leads to a shift from fordist principles of large-scale production and mass-market appeal to post-fordist production, in which a diversified workforce creates products designed for smaller and smaller sub-sets of consumers. As a result of this, consumption becomes a cultural act — a way of asserting your identity, belonging to a particular group or having a certain level of status. Crucially, the idea of consumer freedom is linked to the idea of political freedom, as Slater (1997) argues:

To be a consumer is to make choices: to decide what you want, to consider how to spend your money to get it [...]. 'Consumer souvereignty' is an extremely compelling image of freedom: [...] it provides one of the few tangible and mundane experiences of freedom which feels personally significant to modern subjects. (slater 1997, p27)

According to Slater, this link between consumer choice and political freedom is especially pronounced in the 1980s, when "collective and social provision gave way to radical individualism — as Thatcher put it, 'There is no such thing as a society, only individuals and their families'" (Slater 1997, p10). The idea of individual consumer freedom is pitched as the polar opposite of pre-war ideas of collectivism — the subsequent rejection of modernist housing models isn't much of a surprise. To see how these two conflicts manifest themselves in physcial architecture I'm going to introduce the architectural practice at the Bauhaus, placing it in the wider context of modernist thinking. I will then examine the Dessau-Törten housing settlement near Leipzig, Germany as an example of this practice. Built by Walter Gropius between 1927 and 1930, Törten has been subject to significant alterations by its residents over the last 90 years. By tracking these alterations, I will show how these underlying conflicts shift and overlap over time. In closing, I will examine more recent housing models in the context of a post-industrial economy, again discussing how the conflict between individualism and collectivist ideas is reconciled.

The Myth of the Hero Creator

The emergence of modernism in the beginning of the 20th century coincides with the first wave of feminism. The modernist focus on the machine, speed, efficiency (which were perceived as trditionally male attributes) and opposition of ornament and sentimentality (which were regarded as female) is seen by critics as a reactionary response by male modernists to the new, empowered woman (Dekoven, 2011). We see this reflected in the openly misogynist language of the 1909 futurist manifesto:

We will glorify war—the world's only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman. We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.

(Marinetti, 1909) Here Marinetti is laying out the idea of the heroic, hyper-male creator — a notion that is ultimately reflected in the cult of personality of fascism, which the Futurist movement supported (Blum, 2014). This regressive notion of the authoritarian male artist standss in contrast to the egalitarian aims of the modernist movement, which included the empowerment of women. DeKoven points out:

[...] Male Modernist fear of women’s new power [...] resulted in the combination of misogyny and triumphal masculinism that many critics see as central, defining features of Modernist work by men. This masculinist misogyny, however, was almost universally accompanied by its dialectical twin: a fascination and strong identification with the empowered feminine. (DeKoven, 2011, p. 228)

DeKoven is talking about this contradiction in the context of modernist literature here, but I would argue that her analysis can be expanded to architecture: The figure of the sharply dressed hero architect (be it Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius or Mies van der Rohe) who is literally tasked with designing the new world stands in contrast to the egalitarian, collectivist vision of society the modernist movement was working toward.

From Marinetti to Gropius

It is possible to draw a direct lineage from the Futurist movement to the Bauhaus. In 1910, Adolf Loos echoes Marinetti's denunciation of ornament (though with a Darwinian twist, arguing that "cultural evolution is equivalent to the removal of ornament"). Loos goes on to say that

[...] Ornament is not only produced by criminals; it itself commits a crime, by damaging men's health, the national economy and cultural development. [...] Even greater is the damage ornament inflicts on the workers. As ornament is no longer a natural product of our civilization, it accordingly represents backwardness or degeneration [...] (Loos, 1910)

The notion that ornament is to be overcome in order to achieve progress is reflected in Gropius' 1919 Bauhaus manifesto:

The ornamentation of the building was once the main purpose of the visual arts, and they were considered indispensable parts of the great building. Today, they exist in complacent isolation, from which they can only be salvaged by the purposeful and cooperative endeavours of all artisans.

"The ultimate goal of all art" at the Bauhaus, as Gropius goes on to declare, is architecture. He then explains how "the new building" would unite all artistic disciplines — again echoing the Futurists' denunciation of the past:

So let us therefore create a new guild of craftsmen, free of the divisive class pretensions that endeavoured to raise a prideful barrier between craftsmen and artists! Let us strive for, conceive and create the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture and sculpture and painting, and which will one day rise heavenwards from the million hands of craftsmen as a clear symbol of a new belief to come.' (Gropius, 1919)

It is worth highlighting Gropius' use of mediaeval imagery to talk about the future. The concept of craft guilds, which Gropius refers to in the opening sentence dates back to the 13th century. Further, the "building [...] that will unite every discipline [...] and which will rise heavenwards" is a clear reference to the medieaval cathedral, which is confirmed by Lionel Feininger's woodcut "Cathedral" (1919) used to illustrate the text (Burshart, 2009). Although these mediaeval aesthetics seem opposed to the Marinetti's vision of a mechanised future, the underlying ideas are consistent. There is the denunciation of the past, the rejection of (female) ornamentation in favour of (male) clarity and objectivity. Using almost biblical language, the (male) architect is positioned as a hero figure tasked to build a better society. The contradiction described by DeKoven is perhaps epitomised in Gropius' admission policy: While women were allowed at the Bauhaus (a progressive move in 1919), Gropius made sure they were funneled into the weaving and painting workshops — the architecture department was exclusively male (Droste, 1999).

Architecture at the Bauhaus

Following the revivalist imagery of the manifesto, work at the early Bauhaus was defined by a return to pre-industrial forms. The Sommerfeld House in Berlin (1920, destroyed 1945) with its expressionist wooden decoration, as well as the early furniture of Marcel Breuer and Gunta Stölzl and some of the early pottery are examples of this phase (Bauhaus100, 2017). Christina Lodder places the early Bauhaus as part of a larger artistic movement in search of "spiritual utopia". She argues that "a rejection of materialism and 19th-century positivist outlooks" following the First World War inspired expressionist artists "to infuse [their work] with a spiritual dimension, and to promote the idea that art and architecture were thereby the means of saving mankind from modernity" (Lodder, 2008, p. 24).

The transition to a more rational, technology-focused outlook at the Bauhaus came in 1922 with the arrivals of Theo van Doesburg and Lazlo Moholy-Nagy in Weimar. This new direction was defined by the notion that scientific progress, industrial production and rational decision-making could be employed to solve the "materialism, repressive political structures and glaring social inequalities" of the present (Lodder, 2008, p. 33). From the prespective of modernists, crime, disease, alcoholism and scoial inequality were directly linked to the "overcrowded cities", "old and rotten buildings and poor sanitary conditions" (Le Corbusier, 1923) that industralisation had left behind.

A 1930 film titled 'Die Neue Wohnung' [The New Dwelling] illustrates this idea in striking images (fig. 1). Dark shots of derelict workers' homes are interspersed with scenes of domestic violence and disease. This is then set in contrast to the mdoernist vision of the future: Brightly lit shots of clean interiors with mass-produced, ornament-free furniture. The film ends with a title card announcing: "A better future will hold affordable and humane housing FOR EVERYONE" (Richter, 1930) — emphasizing the aspiration for social equality that imbues modernist thinking.

Figure 1: Video stills from 'The New Dwelling' ['Die Neue Wohnung'], a 1930 film showing the benefits of modernist housing.

Figure 1: Video stills from 'The New Dwelling' ['Die Neue Wohnung'], a 1930 film showing the benefits of modernist housing.

The change in lighting from dark to light in The New Living is no accident: Access to sunlight and air is a central aim of modernist architecture. This can be linked to the belief the benefits of heliotherapy (the idea that sunlight and air could cure diseases), which was widespread in the 1920s, as was the notion that personal hygiene and cleansiness would lead to a better society (Wilk, 2006). We see Gropius implementing these ideas in Törten by using unusually large windows combined with relatively small floorspace, and floors and furniture that would be easy to clean.

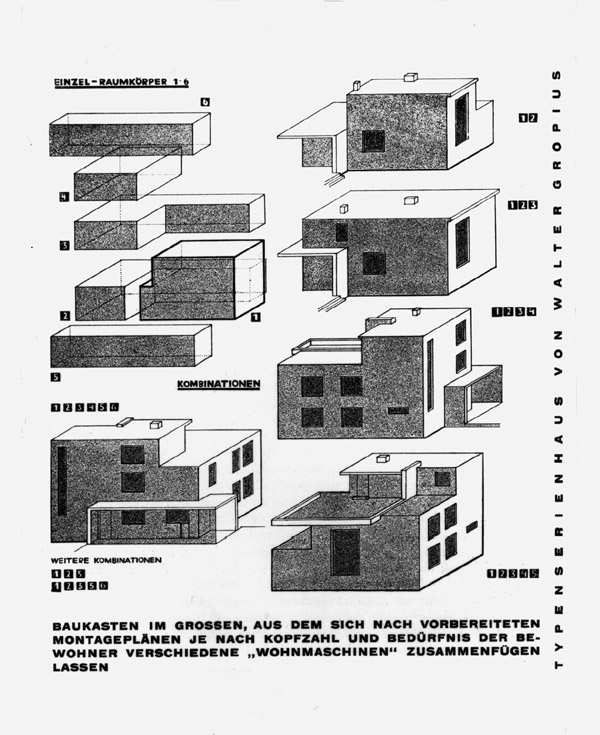

Gropius lays out his own version of these ideas in his 1925 book "Ein Versuchshaus des Bauhauses in Weimar" [A trial building by the Bauhaus in Weimar]. The title refers to the Haus am Horn in Weimar, which was built for the Bauhaus exhibition in 1923. In the introduction Gropius argues that the new age "makes it necessary to finally realise the old idea of building typical dwellinggs cheaper, better and in larger numbers to give every family access to healthy living conditions" (Gropius 1930, page 5). The way to achieve this, according to Gropius is to understand the housing problem "in its entire sociological, economical, technical and formal context". (Gropius 1930, page 5). Gropius also offers specific ideas on how these issues might be addressed. He argues that because most people have similar basic needs, housing should be uniform and mass-produced in specialised factories. Rather than building houses individually at the building site, they should be dry-assembled from premanufactured components using standardised blueprints. Gropius coins the term "large-scale building blocks" ['Baukasten im Grossen'] to describe this form of modular architecture. Figure 2 illustrates this idea: Individual components (labeled 1 through 6) are assembled into different "machines for living" according to the "number and needs of the inhabitants".

Figure 2: Illustration showing the concept of Gropius' "Large-Scale Building Blocks", published in Bauhausbuch 3: Ein Versuchshaus des Bauhauses in Weimar, 1925. Unknown artist, Walter Gropius.

Figure 2: Illustration showing the concept of Gropius' "Large-Scale Building Blocks", published in Bauhausbuch 3: Ein Versuchshaus des Bauhauses in Weimar, 1925. Unknown artist, Walter Gropius.

The artistic challenge, according to Gropius, lies in finding satisfying spatial arrangements of these building blocks. Gropius briefly mentions the idea that contrary to popular belief, smaller, well-lit room might actually lead to better living conditions — again echoing the common belief in the benefits of sunlight. (Gropius, 1930).

The Dessau-Törten Settlement

Over 50 building projects were completed by members of the Bauhaus between 1919 and 1930, and many more after the school disbanded (Engels, 2001). This count includes buildings that were built by Gropius and others relatively independently from the Bauhaus, but some were the result of the type of cross-discipline collaboration that was at the core of the Bauhaus idea. These large-scale projects addressed real-world issues while at the same time serving as classroom experiments at the Bauhaus. A few of these buildings have become instantly recognisable: The Sommerfeld House (referenced above), the Haus am Horn (1923) and the Bauhaus building and Master's houses in Dessau (1925-26). However, it is the lesser-known examples of Bauhaus architecture that might give us the most insight into the conflict between individualism and collectivism. The Dessau-Törten housing settlement in Dessau, Germany is one such example. Unlike other examples of pre-war modernist architecture, Dessau-Törten was subject to significant changes since its construction between 1926 and 1928 (Bauhaus Dessau, 2017). In a form of modern archeology, we can identify different layers of changes made before, during and after the Second World War up to present day. Each layer can give us hints as to how the conflict between modernist ideas and different forms of individualism was reconciled.

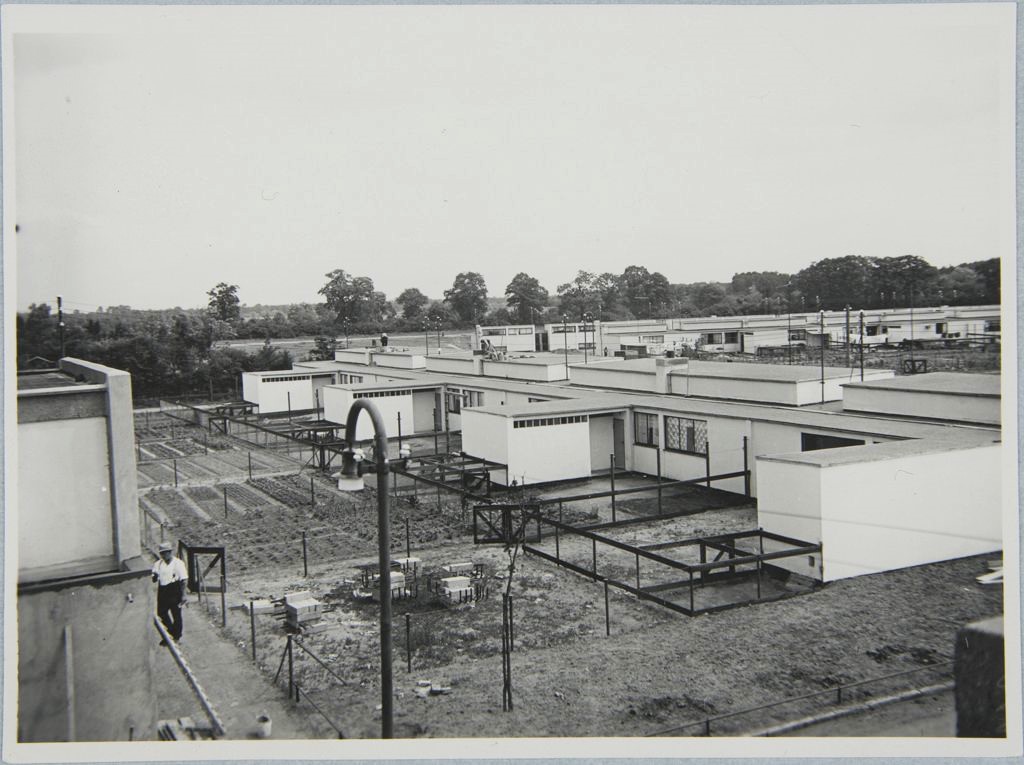

Figure 3: Photograph showing Dessau-Törten shortly after its completion, ca. 1926.

Figure 3: Photograph showing Dessau-Törten shortly after its completion, ca. 1926.

Initial Construction

After a planned housing project in Weimar had failed to materialise (only one building, the Haus am Horn, was ever completed), Törten was the first opportunity for Gropius to put the ideas he had developed during the early 1920s to practice on a large scale. In fact the prospect of building Törten, supported by the social-democratic government of Dessau, was part of the reason Gropius moved the Bauhaus to Dessau in the first place. Dessau, a rising industrial town, had seen an an influx of workers that nearly doubled its population. This led to a housing crisis which the Bauhaus was hoped to address. (Dessau-Törten, 2017) Törten was financed in part by the national government as part of a larger effort to provide affordable housing to lower-income families. Individual units were sold for between RM 9.500 and RM 10.100, or around RM 35 per month — well within the reach of an average industrial worker (Gropius, 1930). The fact that units were sold off to individuals is critical: It allowed homeowners to make changes to their houses with few restrictions.

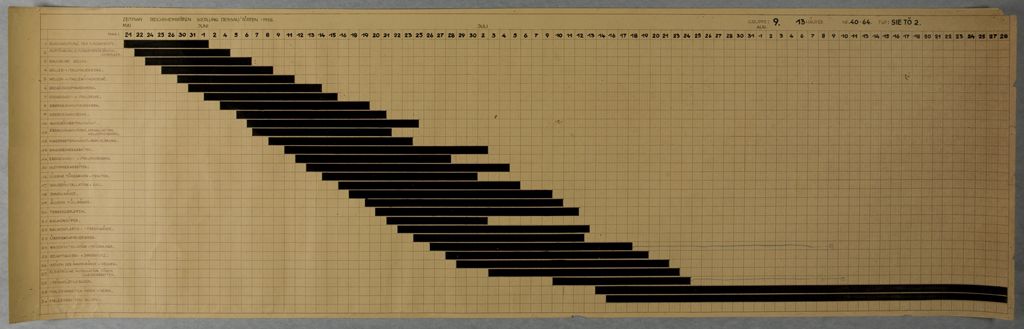

Figure 4: Waterfall chart showing the order of contstruction phases in Dessau-Törten

The settlement served a double, or even triple purpose from the beginning. The Dessau government was hoping for a pragmatic solution to their housing shortage. The national government saw Törten in part as a research project to test new construction methods, granting Gropius additional funds in 1928 to carry out construction experiments and publish the results. Finally, Gropius saw Törten as a way of proving the validity of his vision of architecture, which he had written about for years (Schwarting, 2012).

This triple purpose reflects the conflict at the centre of this essay. One one side is the city of Dessau in a pragmatic effort to provide workers' housing. On the other side is Gropius, the hero architect eager to prove his ideas. We can see Gropius' eagerness reflected in the amount of documents, photographs and films documenting the construction process of Törten. Figure 3 shows what today might be referred to as a waterfall chart. Each bar indicates a specific step in the construction to be carried out at a particular time. This illustrates how Gropius not only designed the architecture, but also the production process and the documentation to fit his vision. He writes about the production process in 1930:

The execution of the shells was done based on a carefully designed plan, in such a way that fixings, wall components and ceiling beams could be manufactured at the building site in a conveyor belt-like process. This method effectively limited loss of time and material [...] (Gropius, 1930)

In addition to the construction process, Fordist production methods also seem to have inspired the visual language of Törten. In addition to familiar clues of modernist architecture (flat roofs, exposed construction through different surface treatments, factory-like steel fixings) Gropius emplys mirrored floor plans, positioning doors and windows of each unit at oppsing edges of the facade. This allows Gropius to effectively blur the line between units, creating the effect of a continuous band rather than a row of individual houses - Le Corbusier's vertical "Machine for Living" becomes a horizontal "living conveyor belt" (Schwarting, 2011). In what we might read as a heroic gesture (by the hero architect), Gropius transforms a pre-existing electrical tower into a monument to technological progress by placing it at the intersection of the two main roads, making it visible from almost every point of the settlement (fig. 3).

Figure 5: Contemporary photograph showing the garden side of row houses in Dessau-Törten.

Figure 5: Contemporary photograph showing the garden side of row houses in Dessau-Törten.

Contrary to the modernist visual language, the urban planning of Törten follows the much earlier concept of the garden city. The notion of the garden city was first proposed by Ebeneezer Howard in 1889, the garden city is based on the idea of individual self-sufficiency for each family (Ward, 1992). In Törten this takes the form of a 400 square metre garden attached to each dwelling (Fig. 3). This runs contrary to the idea of the minimum dwelling that Gropius alludes to in his writings. Rather "rationalising" living functions by centralising them as called for by proponents of the minimum dwelling (Teige, 2012 page 344), the garden city spreads out food production, preparation and recreational space across each individual dwelling.

Figure 6: Contemporary photograph showing a row of houses in Dessau-Törten under construction.

Figure 6: Contemporary photograph showing a row of houses in Dessau-Törten under construction.

Figure 6 shows a section of houses in Dessau-Törten under construction. It highlights the rationalised construction method Gropius designed: Rather than building each house individually, a whole section of identical houses was built at once, allowing for greater efficiency. This photograph is part of an extensive series of professionally-executed photographs documenting the construction process. The fact that such extensive documentation was done can be attributed in part to the experimental nature of Törten — Gropius' experiments had to be documented to be scientifically valid. However, this photograph is more than a neutral document: The two small figures in the background and the dramatic lighting conditions give a monumental scale to the scene. The row of houses continues beyond the right edge of the photograph, reinforcing the effect of an endless conveyor belt. All of this invokes the feeling of optimism and larger-than-life ambition that imbues Gropius' architecture. This image is featured along others in Gropius' 1930 book "Bauhausbauten Dessau", which suggests that Gropius was not only aware of the image, but approved of its message. In addition, a Berlin production company was comissioned to create a documentary showing the construction of the settlement, further underlining Gropius' view of Törten as a vehicle to communicate his ideas (Paulick, 1926).

Alterations before the Second World War

We see the first major deviation from Gropius' plan the day the first families moved in. Few families could afford the RM1350 for Marcel Breuer's specially designed furniture set, so they brought in an ecclectic collection of traditional furniture, wallpapers and curtains, which made an awkward fit in Gropius' small floor plans (Schwarting, 2012). This is perhaps the first instance in which Gropius' ambition runs up against the economic realities of the 1920s.

Following the initial construction, heat insulation quickly became a concern. Anectotal accounts describe how doors and windows would freeze shut during the first winter (Dessau-Törten, 2017). This was a direct result of shortcomings in the design.

-

The steel frame, single glass windows chosen by Gropius were cutting-edge technology at the time. As such, they were not only a third more expensive than traditional wooden windows but also caused major heat loss due to their size and lack of insulation. Most of these windows were replaced smaller, wooden windows within 10 years of the initial construction.

-

The thin outer walls formed another route for heat to escape. This was a direct result of their industrialised production — since the concrete slabs used to build the walls all had the same dimensions, heat bridges could form between the gaps. Homeowners addressed this by erecting secondary brick facades shortly after the initial construction. (Schwarting, 2011)

I would argue that this set of changes can be read as the homeowners' collective response to Gropius' heroic ambitions. Gropius, an established architect, would likely have been aware of the heat insulation issues caused by his choice of construction method and window fittings. The fact he proceeds anyway speaks to the conflict between Gropius' desire to make a clean break with the past and to share his vision of the future and the needs of the people at the centre of that vision. Yes, steel windows might be more expensive now, we could imagine him reasoning, but they will be much cheaper once industrial production has caught up. Gropius says as much in 1930, admitting that it would take the construction industry some time to adjust to the new way of building (Gropius, 1930). In this case, the individualised ownership of the dwellings gives the people upper hand in this conflict.

When the Nazis come to power in the 1930s, they mount a concerted effort to replace all of Gropius' steel windows that still remained. This removed the visual effect of Gropius' "conveyor belt" by re-emphasising the lines between neighbouring houses. The addition of fences, hedges and flower beds between dwellings added to this (Schwarting, 2011).

This came after earlier plans to rebuild Törten from the ground had proven financially unviable and was fashioned into a propaganda victory by the right-wing press at the time. About half an hour up the road, the Bauhaus building itself was surrounded by a grouping of pitched-roof, traditionally-built apartment buildings during this period (Bauhaus building, 2017). While a full survey of fascist aesthetics is beyond the scope of this essay, we can place this coordinated effort to alter existing architecture, emphasising individual expression over the collective in the broader context Nazi propaganda. As Koepnick (1999) points out,

[...] the Nazis followed two different but overlapping strategies. In their pursuit of a homogenous community of the folk, the Nazis made numerous concessions to the popular demand for the warmth of private life and pleasure in a modern media society [...] but simultaneously hoped that the [...] spectacle of modern consumer culture would break the bonds of old solidarities and prepare the atomized individual for the auratic shapes of mass politics, for mass rituals that promised a utopian unification of modern culture (Koepnick, 1999)

This would explain why the Nazi government went to such lengths to remove any visual references to collectivist ideas (i.e. Gropius' "conveyor belt") from Törten. By temporarily encouraging the individualism of modern consumer culture, the government hoped to align people with their totalitarian agenda. Relating this back to theorginal question, I would argue that this point in time marks an overlap between the two definitions of individualism described above. The first definition, based in the image of the violent, energetic male of the Futurist movement is continued in the cult of personality of the fascist state. The second definition, based in the idea of individual "consumer freedom" is deployed here as a propaganda tool to achieve the Nazis' political agenda.

Alterations after the Second World War

Immediately after the war, a number of buildings in Törten had to be rebuilt - Dessau, being the site of a Junkers aeroplane factory had become a bombing target. Since little building material was available, many original components were re-used. As the economic situation stabilises, the conflict between the collectivist ideals of modernism and individualism as defined to post-war comsumerism becomes more prevalent — even as Törten exists within the socialist regime of the GDR. As the economic situation stabilises in the 1950s, people's focus turnes toward expanding their living space. Houses were expanded into the garden (which was no longer needed for food production), and in many cases the roof terrace in the back was enclosed to create an additional room (Schwarting, 2011).

Figure 7: 1965 photograph showing a row of houses in Törten equipped with long aerials to receive West-German television

Figure 7: 1965 photograph showing a row of houses in Törten equipped with long aerials to receive West-German television

One of the more memorable images from this time (fig. 7) shows a row of houses, each equipped with a tall aerial used to illegally receive West-German television. This is in a way a reversal of the earlier power structure: Rather than implementing a set of political ideals from the top down through architecture (as Gropius had done), individuals are making an architectural intervention to subvert restrictions imposed by a socialist state. According to Husemann (2016), this was a fairly widespread act of disobedience against the government, with up to 85% of the GDR population receiving West-German television. In terms of the conflict between collectivism and individualism, I read this as a victory of the latter: Individual residents, empowered by increasing wealth and education are satisfying their growing demand for diverse entertainment in an act of direct action against an authoritarian state. During this period the use of the gardens also changes substantially. As the need for individual food production becomes less pronounced, the gardens take up a more recreational role. The space is also used to accomodate the increasing number of private cars in the settlement. Car ownership in the GDR increased drastically from 0.2 cars per 100 housholds in 1955 to 40 in 1982 (Edwards, 1985). In response to this, many home-owners build garages and carports along the back edge of their property, transforming the gravel path between opposing gardens into a secondary road. Like earlier alterations, these additions appear to be largely done on an individual basis, forming an ecclectic array of architectural styles. Again, the spread of cars as a means of individualised transport and personal expression can be read as a victory of modern consumerism over the collectivist ideas of the 1920s.

Alterations after 1989

Another significant set of changes to Törten come after the collapse of the GDR, which suddenly gives residents access to an abundance of tools and building materials through DIY-retail, which had grown to a substantial industry since the 1960s. The early 1990s coincide with a period of increased globalised competition, forcing retailers to drop prices and make products accessible to a wider group of consumers (Gelber, 1999).

Figures 8 through 12 show the variety of doors, windows, house numbers, landscaping, facade materials and seasonal decorations that define the Törten settlement today. Figure 8 shows one of two dwellings that remain almost entirely in the original 1928 condition — Compared with Figures 9 through 11, it illustrates the degree of visual diversification that has taken place over the last 90 years.

Figure 8: Photograph showing the house at 38 Mittelring, one of two dwellings remaining close to the original condition.

Figure 8: Photograph showing the house at 38 Mittelring, one of two dwellings remaining close to the original condition.

Figure 9: Photograph showing a dwelling in Dessau-Törten with layers of architectural alterations including facade material, roofing, windows and landscaping.

Figure 9: Photograph showing a dwelling in Dessau-Törten with layers of architectural alterations including facade material, roofing, windows and landscaping.

Figure 10: Photograph showing a dwelling in Dessau-Törten with layers of architectural alterations including facade material, roofing, windows and landscaping.

Figure 10: Photograph showing a dwelling in Dessau-Törten with layers of architectural alterations including facade material, roofing, windows and landscaping.

Figure 11: Photograph showing a dwelling in Dessau-Törten with layers of architectural alterations including facade material, roofing, windows and landscaping.

Figure 11: Photograph showing a dwelling in Dessau-Törten with layers of architectural alterations including facade material, roofing, windows and landscaping.

There is a case to be made that these alterations are in some sense a continuation of Gropius' idea of modular architecture. DIY-retail makes mass-manufactured tools and building components accessible to large parts of the population. Produced in standard dimensions and in numbers Gropius' couldn't have imagined, these components can largely be assembled by homeowners with little specialist knowledge. Gropius' construction method, in which only the side walls are load-bearing makes chnages to the floor plan relatively easy. Though contrary to Gropius vision of a dwelling that responded to the functional needs of its residents, the majority of the most recent changes are acts of individual cultural expression in line with Slater's (1997) definition of consumerism.

Figure 12: Photographs showing the variety of front doors in Dessau-Törten. The top left photograph shows the door of 35 Doppelreihe, which is the only original 1920s door remaining in the settlement.

Figure 12: Photographs showing the variety of front doors in Dessau-Törten. The top left photograph shows the door of 35 Doppelreihe, which is the only original 1920s door remaining in the settlement.

Figure 13: Signage in Dessau-Törten pointing to (from top to bottom): Hannes Meyer's Konsum Building, various points of architectural significance, an orthopedic clinic and a pharmacy. The structure in the background is the electrical tower at the centre of the settlement.

Figure 13: Signage in Dessau-Törten pointing to (from top to bottom): Hannes Meyer's Konsum Building, various points of architectural significance, an orthopedic clinic and a pharmacy. The structure in the background is the electrical tower at the centre of the settlement.

With the increasing public recognition of the Bauhaus and its architectural output in the 1980s, public education has become a permanent part of the Törten settlement. In 1992 the first house was restored to its original state by a private foundation. Since then, a number of houses have been restored to various degrees by either the local government or their respective owners (bauhaus-dessau.de, 2017). (The notion of "original state" here is debatable — it is often impossible to discern exactly which materials and construction methods were used during construction).

This latest development can be read as a reponse to the emergence of the post-industrial society, in which services (including health and education) replace manufacturing as the primary means of generating capital. This transition is perhaps epitomised by the large sign which now stands in front of the cenral electrical tower in Törten (fig. 14). The top two signs point to a permanent exhibition documenting the history of the estate (housed since 2011 in Hannes Meyer's Konsum Building) and various architectural points of interest in the settlement, respectively (Moller, 2017). The bottom two signs point to an orthopedic clinic and a pharmacy, serving the largely retirement-age community of Törten. This neatly sums up the developments we'll examine in the following chapter, turning away from Törten to more recent forms of collectivist housing.

Collectivist housing models in the post-industrial society

Modernist social housing was in many ways a response to the emergence of a new social class: the industrial worker. After the First World War rising industrial towns like Dessau attracted a large number of workers, leading to a sudden population increase the existing housing and infrastructure was unfit to handle. This led to the poor living conditions modernist architects recognised and attempted to improve through large-scale urban developments. As Bell (1999) shows, we are now at a similar moment of transition — from an industrial society to a post-industrial one. According to Bell, this transition is marked by a number of factors: Sercives replace agriculture and manufacturing as the primary source of employment ("services" meaning transportation and logistics, as well as education and healthcare). Further, the importance of physical infrastructure (roads, trains) decreases as intellectual infrastructure (internet connections, computing power) becomes critical to economic productivity.

As the industrial revolution created the industrial worker, the transition to a post-industrial society is likely to create new classes of people with new housing needs.

We can see this process happening in front of us already. Simpson (2015) describes a new class of people created entirely by scientific progress and the abundance of services in the post-industrial age: the "Young-Old". First described by Bernice Neugarten in 1974, the Young-Old are people at retirement age with higher purchasing power, higher likelihood living independently from their families, more education and better health status than those previously in their age group. According sociologist Andrew Blaikic (1999, cited in Simpson, 2015, p. 13), the Young-old might be the first large demographic group in history "whose daily experience [does] not consist of work or schooling [...]"

According to Simpson, the emergence of the Young-Old can be linked to two factors aligned with Bell's analysis of the post-industrial society. First, advances in public health, nutrition and the decline of manual labour has led to an increased life expectancy in both industrial and developing countries — doubling from 40 years in 1840 to 80 years in 2000. Medical products developed over the last century, such as the artificial hip, the contact lens, electronic hearing aids and Viagra extend the physical capabilities of the body. This increased importance of the medical sector is in line with Bell's model, which describes a shift to a primarily service-based economy. Secondly, the decline of the multi-generational family creates a class of retirees that has to be more self-reliant than previous generations. Again this can be linked to Bell's description of post-industrialism: "Intellectual Work" can be done independently from any physical location. This in turn creates what Simpson describes as the "[increased] mobility requirements of the modern workforce, which drives people apart geographically" (Simpson, 2015, p. 45).

While in the 19th century the invention of the steam engine and Fordist production methods brought about the industrial worker, it is scientific progress and the shift from industrial to intellectual work that leads to the emergence of the Young-Old. They have the desire, health and financial means to live independently, which makes the institutional homes of previous generations unfit for their needs. At the same time, shifts in the labour market and changes in family values have made the traditional model of the multi-generational household unavailable (or undesirable). The only response to this new class of people would appear to be the development of new housing models.

Simpson describes a number of these new models, the most striking of which is perhaps the "The Villages", a vast retirement community outside Orlando, Florida. With a population of 119.000 in 2016 (Schneider, 2016), The Villages are not only the largest retirement community in the world, but America's fastest growing city overall. In many ways, they bear a striking resemblance to the social housing developments of the 1920s: Houses are mass-produced and laid out following a preconceived plan. Transportation, architectural vernacular, healthcare, local history, media and (by way of age and income segregation) the social fabric of the settlement are part of a "Gesamtkunstwerk" of a scope far beyond what the modernists were able to do. Here the hero architect of the 1920s is replaced by the faceless, owner-less development corporation of post-war capitalism.

The developers of The Villages deploy a complex architectural system to create a specific "lifestyle experience". TO mask the industrial scale of the settlement, it is split up into smaller "towns", each with its own, entirely fabricated local history. The developers use techniques developed in theme parks to artificially age buildings, and even go so far as to install fictional historical artifacts and historical plaques to create a feeling of local history. All of this is done (to some success) to encourage the kind of social interaction between residents that represents an idealised idea of life in a small town. The designers are surprisingly candid about this:

[...] We write storylines that we use, and that comes from my theme park background. The storyline acts as your concept, you go back to it to design facades. It's funny, we make up stories for some of these buildings and some of the residents think they're real. They don't even know any better because we even go to the trouble of paining old graphics on the buildings and people think that's an old general store when it really isn't. (Simpson, 2015 page 207)

The primary means of transportation in the villages is the golf cart. This is another specific design decision by the developer: The golf cart bridges the gap between the automobile (which is costly, associated with the working life and requires a licence, which residents may have lost or never acquired in the first place) and the mobility scooter (which is slow and associated with the frailty of old age). The developer encourages golf cart use by making specific golf cart roads, bridges and tunnels part of the urban planning, and incorporating golf cart-related events (such as parades) into the social programme. This is reiterated by The Village's marketing material which often describes points of interest being "only a short golf cart ride away" (The Villages, 2017).

We find the notion of using architectural intervention to design social interaction on a much smaller scale in the work of Hannes Meyer (who succeeded Gropius as Bauhaus director in 1928): His ADGB Trade Union School near Berlin (1928-1930) is designed to break students into groups of four — this was thought to be the ideal number to accomodate learning.

In another echo of the 1920s, we find the notion of heliotherapy reflected The Villages marketing material, for instance these song lyrics from a 2011 video advert showing landscape shots and residents interacting in bright sunlight:

It's a little slice of paradise / Sunshine and golf galore / Neighbours stroll the old town square / And the good life is in store / The Villages / Where the sun shines all year round / The Villages / Florida's friendliest hometown / From our family to yours / From our family to yours / Come on / Come on down / We're Florida's friendliest hometown

(The Villages Florida, 2011).

How do the villages reconcile the confilct between their essentially collectivist design with their residents' desire for individualism (which compelled them to move out of the multigenerational household in the first place)? I would argue that the developer achieves this by what is essentially marketing. They emphasise the benefits of the collectivist settlement (centralised access to healthcare, unified transportation, social cohesion) while creating the perception of individual freedom and self-governance — sometimes in the same TV commercial.

Figure 14: Photograph showing customised golf carts in the villages displayed as part of a developer-supported christmas parade.

Figure 14: Photograph showing customised golf carts in the villages displayed as part of a developer-supported christmas parade.

I would argue that part of the reason this succeeds is the overwhelming scale of The Villages: With 2.400 organised clubs (one for every 65 residents), hundreds of sport facilities and thousands of planned events a month (125 on the day of this writing alone) the developers are able to create an environment in which individual choice seems unlimited. This perception of individual freedom is reinforced through carefully planned pockets of individual expression, such as residents decorating their golf carts (fig. 14) — perhaps analogous to the facade coverings, landscaping and seasonal decorations used as a means of cultural expression in Törten. In cases like this, the developer gives up direct design control — though the results are fed back (in the form of developer-sponsored parades and features in developer-funded local media) into the larger lifestyle experience the developer is attempting to sell.

Conclusion

We've established that the conflict between individualism and the collectivist ideals of modernism is twofold, depending on how it is framed. Following the feminist critique of modernism, we've seen how the figure of the male hero architect stands in conflict with the egalitarian aims of the modernist movement. We've seen this conflict played out in Walter Gropius' Dessau-Törten housing settlement, where he makes design decisions aimed at showing his vision of the future rather than addressing the pragmatic needs of the present. This is reconciled by individual residents reverting their houses back to earlier construction methods (by replacing steel windows with wooden ones and erecting brick facades).

In a strange overlap between our two definitions of individualism, the Nazi government removes many of the visual clues representing collectivist ideas in Törten. However this is in line with the contradictory methods of Nazi propaganda, which leverages early forms of consumerism to make the population more receptive to their authoritarian agenda.

After the Second World War, the conflict between individualism and collectivism shifts from inside the modernist movement to the outside world and the emerging figure of the modern consumer. The architectural interventions in Törten are evidence of a decade-long negotiation between the collectivist vision of modernism and people's post-Fordist demand for cultural self-expression.

The transition to a post-industrial society has created a demand for new forms of housing. The Villages of Florida are a vivid example of this. With their heavily programmed lifestyle, centralised medical care, transportation and mass-produced housing, they might be described as the urban manifestation of a kind of "leisure socialism" (Simpson, 2015, p 246). Here the figure of the hero architect of the 1920s is replaced by the owner-less corporation of the 1980s.

I will end by arguing that the continued transition to a post-industrial economy will likely create more demand for new forms of housing. A re-examination of modernist ideas of social housing might be part of this debate, in line with a broader re-examination of socialist ideas following a disillusionment with the results of economic liberalism (which led to the rejection of modernst housing models in the first place), especially among younger generations. Shrimpton et. al (2017) sums up this growing sense of anxiety, showing that

[...] Britons no longer think young people will have a better life than previous generations, with only around one quarter (23 per cent) of adults taking this view. Instead, roughly half (48 per cent) believe that millennials will have a worse life than their parents.

Indeed, emerging writers like Owen Hatherley ("Militant Modernism", 2009) and researchers like Peter Chadwick ("This Brutal World", 2016) are already working to change the public perception of modernist housing. This development can only be welcomed. However I would take the position that in addition to a re-examination of modernist housing models, entirely new modes of living might be needed. In an economy that relies increasingly on intellectual labour done by a geographically independent workforce, perhaps this offhand remark made by Gropius in 1925 (six years before the first caravan was manufactured in Germany) might gain new importance (Gunkel, 2011):

Perhaps "mobile living-shells" ["mobile Wohngehause"], allowing us to take with us all the conveniences of a real [traditional] living standard even through relocations, are no longer too far-fetched a utopia. (Gropius, 1925 p5 )